"Gather a branch from any of the trees or flowers to which the earth owes its principal beauty. You will find that every one of its leaves is terminated, more or less, in the form of the pointed arch; and to that form owes its grace and character. I will take, for instance, a spray of the tree which so gracefully adorns your Scottish glens and crags—there is no lovelier in the world—the common ash. Here (fig.4) is a sketch of the clusters of leaves which form the extremity of one of its young shoots. Observe, they spring from the stalk precisely as a Gothic vaulted roof springs, each stalk representing a rib of the roof, and the leaves its crossing stones; and the beauty of each of those leaves is altogether owing to its terminating in the Gothic form, the pointed arch. Now do you think you would have liked your ash trees as well, if Nature had taught them Greek, and shown them how to grow according to the received Attic architectural rules of right? I will try you. Here is a cluster of ash leaves, which I have grown expressly for you on Greek principles (fig. 6). How do you like it?"

I have now got Ruskin Spectacles on as I walk around Festival Edinburgh. Today the new entrance to Waverley Station was opened. Ruskin described it precisely:

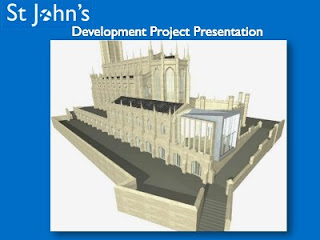

And then there is this description of how we put up a new building which reminded me irresistibly of my church's proposed 'development', which will remove my favourite suntrap terrace in Edinburgh and replace it with an oversized porch at a cost out of all proportion to any other church activity:

There are several buildings in Edinburgh, built between perhaps 1870 and 1940 - the National Portrait Gallery, the war memorial chapel in Edinburgh Castle and Fairmilehead Parish Church for example -- which I'm sure were fairly directly inspired by the Ruskin mindset. Ruskin has his cons as well as his pros -- he talks some right rubbish sometimes. But I wouldn't mind if the current architects of Edinburgh were a little more inspired by his nature-inspired, anti-pretentious, thinking.

I once thought his 'seven lamps' of architecture a mantra worth committing to memory: Truth, beauty, power, memory, sacrifice, obedience, life. There's a test for soundness in a building -- or a person!

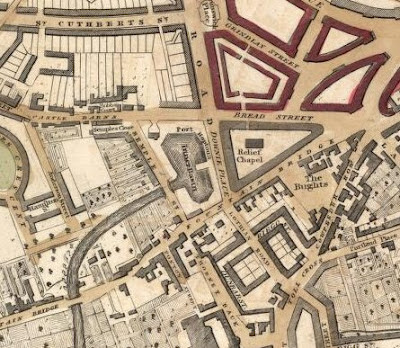

Well, but, you will answer, you cannot feel interested in architecture: you do not care about it, and cannot care about it. I know you cannot. About such architecture as is built nowadays, no mortal ever did or could care. You all know the kind of window which you usually build in Edinburgh: here is an example of the head of one: a massy lintel of a single stone, laid across from side to side, with bold square-cut jambs—in fact, the simplest form it is possible to build. It is by no means a bad form; on the contrary, it is very manly and vigorous, and has a certain dignity in its utter refusal of ornament. But I cannot say it is entertaining. How many windows precisely of this form do you suppose there are in the New Town of Edinburgh? And your decorations are just as monotonous as your simplicities. How many Corinthian and Doric columns do you think there are in your banks, and post-offices, institutions, and I know not what else, one exactly like another?—and yet you expect to be interested!

And then there is this description of how we put up a new building which reminded me irresistibly of my church's proposed 'development', which will remove my favourite suntrap terrace in Edinburgh and replace it with an oversized porch at a cost out of all proportion to any other church activity:

In your public capacities, as bank directors, and charity overseers, and administrators of this and that other undertaking or institution, you cannot express your feelings at all. You form committees to decide upon the style of the new building, and as you have never been in the habit of trusting to your own taste in such matters, you inquire who is the most celebrated, that is to say, the most employed, architect of the day. And you send for the great Mr. Blank, and the Great Blank sends you a plan of a great long marble box with half-a-dozen pillars at one end of it, and the same at the other; and you look at the Great Blank's great plan in a grave manner, and you dare say it will be very handsome; and you ask the Great Blank what sort of a blank check must be filled up before the great plan can be realized; and you subscribe in a generous "burst of confidence" whatever is wanted; and when it is all done, and the great white marble box is set up in your streets, you contemplate it, not knowing what to make of it exactly, but hoping it is all right; and then there is a dinner given to the Great Blank, and the morning papers say that the new and handsome building, erected by the great Mr. Blank, is one of Mr. Blank's happiest efforts, and reflects the greatest credit upon the intelligent inhabitants of the city of so-and-so; and the building keeps the rain out as well as another, and you remain in a placid state of impoverished satisfaction therewith; but as for having any real pleasure out of it, you never hoped for such a thing. If you really make up a party of pleasure, and get rid of the forms and fashion of public propriety for an hour or two, where do you go for it? Where do you go to eat strawberries and cream? To Roslin Chapel, I believe; not to the portico of the last-built institution.

There are several buildings in Edinburgh, built between perhaps 1870 and 1940 - the National Portrait Gallery, the war memorial chapel in Edinburgh Castle and Fairmilehead Parish Church for example -- which I'm sure were fairly directly inspired by the Ruskin mindset. Ruskin has his cons as well as his pros -- he talks some right rubbish sometimes. But I wouldn't mind if the current architects of Edinburgh were a little more inspired by his nature-inspired, anti-pretentious, thinking.

I once thought his 'seven lamps' of architecture a mantra worth committing to memory: Truth, beauty, power, memory, sacrifice, obedience, life. There's a test for soundness in a building -- or a person!